Before I share my experience, I’d like to call in my ancestors, particularly the women, as what I write will give name to people whose actions and words have been harmful to my community: Francisca Garcia, Epigmenia Saucedo, Andrea Esparza Limon, Petra Limon Olvera, Maria Guadalupe Olvera Torres. I share their names in honor of their lives and in recognition of their struggle to nourish, protect and love.

At the top of the new year, I had the pleasure of representing Food and Farm Communications Fund at the Oxford Real Farming Conference (ORFC) in the United Kingdom to discuss rematriation and the power of story.

We at FFCF understand that rematriation is a political term used in the U.S. specifically to describe land reclamation while centering Indigenous women in in the process. Rematriation is an opportunity to recognize that centuries-long Indigenous practices are a way forward, instead of claiming that we are creating a new model for food and land sovereignty. As an organization, narrative change is a core strategy of our work. We work alongside our grantee partners to amplify their messages, campaigns and efforts around food and farming systems change in order to foster equity in the food space, and also sustainable food-centered resources for communities across the country. So bringing this message to a global audience at ORFC, which was attended by nearly 5,000 delegates from over 130 countries, was an opportunity we could not pass up.

L-R Kelly Carlisle, Esperanza Pallana, Rubi Orozco Santos

What made this experience even more meaningful was that our panel, aptly titled Unceded Voices*: Rematriating the Narrative, was a collaboration with Castanea Fellowship and featured fellows and colleagues, Kelly Carlisle of Acta Non Verba Youth Urban Farm and Rubi Orozco Santos of La Semilla Food Center. It was such a pleasure hearing Kelly speak about how Acta Non Verba launched with the intention of inspiring youth to know where their food came from and to embrace farming as a potential career path, especially for Black youth who don’t often see this as a path to follow. Similarly, Rubi shared La Semilla’s goal to revitalize heritage foodways, of pre-colonial Mexico and the Southwest U.S., by preserving the practice of oral tradition with elders. They both shared how they utilize storytelling culture to uplift healthy food traditions to increase connection within ecosystems, and shift power through policy and financial literacy.

Hearing Kelly and Rubi’s narratives reminded me of my own story of food culture and rematriation. I recalled how at the turn of the 20th century many Mexicans were recruited by American companies to cross the colonial border for work. My own ranching family based in Los Altos de Jalisco, was experiencing a severe drought on their land and was recruited by Asarco lead smelter run by the powerful U.S. family, the Guggenheims. This recruitment increased during the Mexican Revolution. At this tumultuous time, 10% of the Mexican population departed for the U.S. and another 8% perished from impacts of war. The neighboring U.S. saw another opportunity to exploit Mexican labor. The sudden influx of Mexicans caused a range of reactions. Some, like Arthur G. Arnoll, general manager of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce and George P. Clements, head of agriculture for the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, believed in eugenics1 and thought Mexican bodies were better suited for labor than white bodies. They fought legislatively to protect their right to cheaply employ Mexicans. At the same time, the national Americanization Movement began. The Americanization movement was originally started by non-profits but grew to include government subsidies, public educational policy changes, and the creation of national holidays.2

L-R BACK, ANDREA ESPARZA LIMON, PETRA LIMON OLVERA, MARIA CRUZ LIMON, MARIA SIXTA LIMON NEWTON, NAMES UNKNOWN (CHILD WITH HEAD DOWN IS MARGARITO OLVERA), IN FRONT OF THE SANTA FE RAILROAD LABOR CAMP KITCHEN WHERE THEY WORKED, NEWTON, KANSAS.

During this era, texts of disinformation like “Americanization Through Homemaking” by the Americanization teacher, Pearl Idelia Ellis, became commonplace in educational institutions across the nation. Ellis believed our native diet promoted our “inherent” criminality. Ellis categorized tortillas, chiles, and beans, as “accelerators of criminal tendencies” and wrote:

The noon lunch of the Mexican child quite often consists of a folded

tortilla with no filling. There is no milk or fruit to whet the appetite.

Such a lunch is not conducive to learning. The child becomes lazy.

His hunger unappeased, he watches for an opportunity to take food from

the lunch boxes of more fortunate children. Thus the initial step in a

life of thieving is taken.

(1929: 26-27)

In fact, some believed that it was critical to target the women and children in our communities to be successful with these programs. Alfred White, another Americanization teacher, wrote, “Go after the woman should be the slogan…The children of these foreigners are the advantages to Americans, not the naturalized foreigners. These are never 100% Americans, but the second generation may be. ‘Go After the woman’ and you may save the second generation for America.”3

-

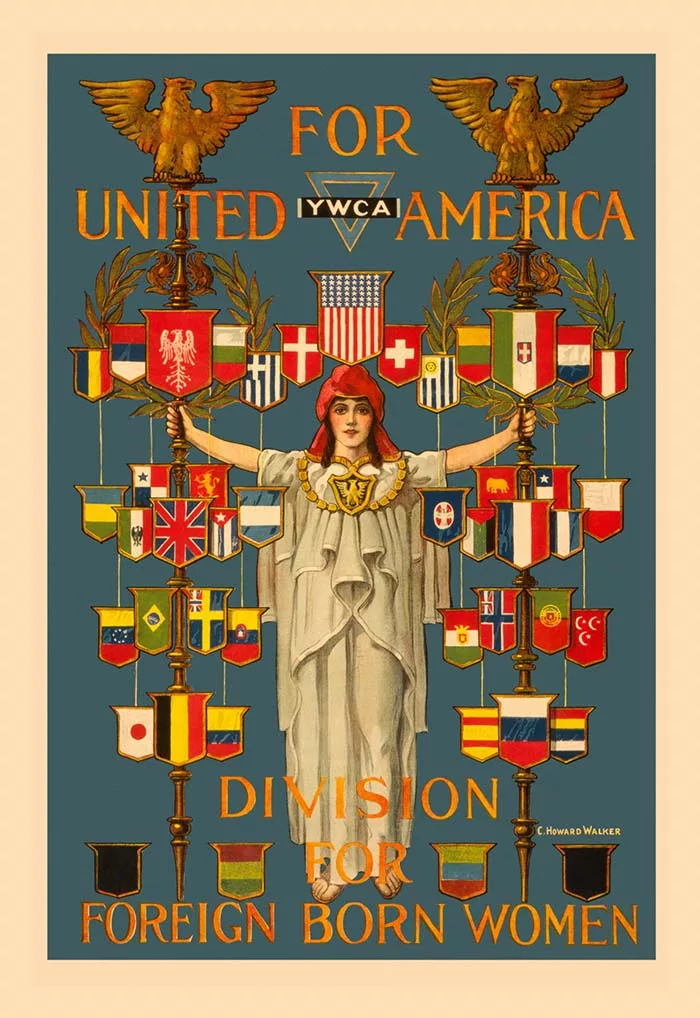

Propaganda campaign targeting immigrant women. YWCA was a partner of the U.S. Americanization programs that targeted women, families and their home culture.

These anecdotes allowed me, and the audience, to see that though the historical fracturing of our relationship with our Indigenous foods is deeply wounding, today we are witnessing folks all across the country (and world) reclaim Indigenous foodways and restore these practices. We know that our effort to reclaim corn and other foods is part of that act of rematriating. It is bringing that ancestral voice back, lifting it up, and emphasizing the sacredness of it. And though we begin with food, at the end of the day, this is about our connection to a greater ecosystem of land, culture and community.

(L-R Anna Sulan Masing, Kelly Carlisle, Esperanza Pallana, Rubi Orozco Santos)

I would be remiss to not point out that our panel was led by Anna Sulan Masing, a Malaysian-New Zealander based in London. Anna is an academic and journalist that writes on Indigenous identity. She is also the host of Taste of Place, a Whetstone Radio Collective podcast that explores colonialism, traces trade routes, meets pepper farmers, discovers spice molecules and delves into the mysteries of perfume. Whetstone Radio Collective was also a 2021 recipient of FFCF’s Impact Media Awards. Our session was also one of many featured where one could learn about the revitalization of land-based spiritual practices, ritual and plant medicine. We shared space with powerful voices including Vananda Shiva, who in 1992, published Women's Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation. In this article she stated “Diversity is the price paid in the patriarchal model of progress which pushes inexorably towards monocultures, uniformity, and homogeneity.”

I could not imagine a more apt location than Oxford, England, to offer this presentation. The words of culture change leader, Bridget Antionette Evans, came to me- “narrative oceans.” We currently swim in a narrative ocean that claims the ends justifies the means. This ocean is teeming with disinformation and devastating ideas about who we are, who belongs, and who does not.

We could not have been in better company. We invite you to listen to our session!

*Our title Unceded Voices was inspired by Unceded Voices : anti Colonial Street Art Convergence. This convergence of Indigenous women and women of color, in Tiotia: ke (so called Montréal), unceded Kanien’kéhá:ka (Mohawk) and Algonquin territories, reclaimed public space to share their art-works.

- Unwanted Mexicans Americans in The Great Depression by Abraham Hoffman

- https://www.cato.org/blog/failure-americanization-movement

- Alfred White, "The Apperceptive Mass of Foreigners as Applied to Americanization, the Mexican Group" (master's thesis, University of California, 1923), p. 30.

Latest News

Holiday Gift Guide 2025

Voices of Climate Justice and Democracy